Kakeya set

In mathematics, a Kakeya set, or Besicovitch set, is any set of points in Euclidean space which contains a unit line segment in every direction. While many types of objects satisfy this property, several interesting results and questions are motivated by considering how small such sets can be. Besicovitch showed that there are Besicovitch sets of measure zero.

A Kakeya needle set (sometimes also known as a Kakeya set) is a (Besicovitch) set within which a unit line segment can be rotated continuously through 180 degrees, returning to its original position with reversed orientation. Besicovitch showed that there are Kakeya needle sets of arbitrarily small positive measure.

Contents |

Kakeya needle problem

The Kakeya needle problem asks whether there is a minimum area of a region D in the plane, in which a needle can be turned through 360°. This question was first posed, for convex regions, by Soichi Kakeya (1917).

He seems to have suggested that D of minimum area, without the convexity restriction, would be a three-pointed deltoid shape. The original problem was solved by Pál.[1] The early history of this question has been subject to some discussion, though.

Besicovitch sets

Besicovitch[2] was able to show that there is no lower bound > 0 for the area of such a region D, in which a needle of unit length can be turned round. This built on earlier work of his, on plane sets which contain a unit segment in each orientation. Such a set is now called a Besicovitch set. Besicovitch's work showing such a set could have arbitrarily small measure was from 1919. The problem may have been considered by analysts before that.

One method of constructing a Besicovitch set can be described as follows (see figure for corresponding illustrations). The following is known as a "Perron tree" after O. Perron who was able to simplify Besicovitch's original construction:[3] take a triangle with height 1, divide it in two, and translate both pieces over each other so that their bases overlap on some small interval. Then this new figure will have a reduced total area.

Now, suppose we divide our triangle into eight subtriangles. For each consecutive pair of triangles, perform the same overlapping operation we described before to get four new shapes, each consisting of two overlapping triangles. Next, overlap consecutive pairs of these new shapes by shifting their bases over each other partially, so we're left with two shapes, and finally overlap these two in the same way. In the end, we get a shape looking somewhat like a tree, but with an area much smaller than our original triangle.

To construct an even smaller set, subdivide your triangle into, say,  triangles each of base length

triangles each of base length  , and perform the same operations as we did before when we divided our triangle twice and eight times. If the amount of overlap we do on each triangle is small enough and the size

, and perform the same operations as we did before when we divided our triangle twice and eight times. If the amount of overlap we do on each triangle is small enough and the size  of the subdivision of our triangle is large enough, we can form a tree of area as small as we like. A Besicovitch set can be created by combining three rotations of a Perron tree created from an equilateral triangle.

of the subdivision of our triangle is large enough, we can form a tree of area as small as we like. A Besicovitch set can be created by combining three rotations of a Perron tree created from an equilateral triangle.

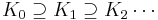

Adapting this method further, we can construct a sequence of sets whose intersection is a Besicovitch set of measure zero. One way of doing this is to observe that if we have any parallelogram two of whose sides are on the lines x=0 and x = 1 then we can find a union of parallelograms also with sides on these lines, whose total area is arbitrarily small and which contain translates of all lines joining a point on x=0 to a point on x = 1 that are in the original parallelogram. This follows from a slight variation of Besicovich's construction above. By repeating this we can find a sequence of sets

each a finite union of parallelograms between the lines x=0 and x = 1, whose areas tend to zero and each of which contains translates of all lines joining x=0 and x = 1 in a unit square. The intersection of these sets is then a measure 0 set containing translates of all these lines, so a union of two copies of this intersection is a measure 0 Besicovich set.

There are other methods for constructing Besicovitch sets of measure zero aside from the 'sprouting' method. For example, Kahane[4] uses Cantor sets to construct a Besicovitch set of measure zero in the two-dimensional plane.

Kakeya needle sets

By using a trick of Pál, known as Pál joins (given two parallel lines, any unit line segment can be moved continuously from one to the other on a set of arbitrary small measure), a set in which a unit line segment can be rotated continuously through 180 degrees can be created from a Besicovitch set consisting of Perron trees.[5]

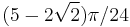

In 1941, H. J. Van Alphen[6] showed that there are arbitrary small Kakeya needle sets inside a circle with radius  (arbitrary

(arbitrary  ). Simply connected Kakeya needle sets with smaller area than the deltoid were found in 1965. Melvin Bloom and I. J. Schoenberg independently presented Kakeya needle sets with areas approaching to

). Simply connected Kakeya needle sets with smaller area than the deltoid were found in 1965. Melvin Bloom and I. J. Schoenberg independently presented Kakeya needle sets with areas approaching to  , the Bloom-Schoenberg number. Schoenberg conjectured that this number is the lower bound for the area of simply connected Kakeya needle sets. However, in 1971, F. Cunningham[7] showed that, given

, the Bloom-Schoenberg number. Schoenberg conjectured that this number is the lower bound for the area of simply connected Kakeya needle sets. However, in 1971, F. Cunningham[7] showed that, given  , there is a simply connected Kakeya needle set of area less than

, there is a simply connected Kakeya needle set of area less than  contained in a circle of radius 1.

contained in a circle of radius 1.

Although there are Kakeya needle sets of arbitrarily small positive measure and Besicovich sets of measure 0, there are no Kakaya needle sets of measure 0.

Kakeya conjecture

Statement

The same question of how small these Besicovitch sets could be was then posed in higher dimensions, giving rise to a number of conjectures known collectively as the Kakeya conjectures, and have helped initiate the field of mathematics known as geometric measure theory. In particular, if there exist Besicovitch sets of measure zero, could they also have s-dimensional Hausdorff measure zero for some dimension s less than the dimension of the space in which they lie? This question gives rise to the following conjecture:

-

- Kakeya set conjecture: Define a Besicovitch set in Rn to be a set which contains a unit line segment in every direction. Is it true that such sets necessarily have Hausdorff dimension and Minkowski dimension equal to n?

This is known to be true for n = 1, 2 but only partial results are known in higher dimensions.

Kakeya maximal function

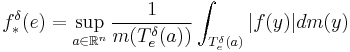

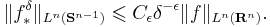

A modern way of approaching this problem is to consider a particular type of maximal function, which we construct as follows: Denote Sn-1 ⊂ Rn to be the unit sphere in n-dimensional space. Define  to be the cylinder of length 1, radius

to be the cylinder of length 1, radius  , centered at the point a ∈ Rn, and whose long side is parallel to the direction of the unit vector e ∈ Sn-1. Then for a locally integrable function f, we define the Kakeya maximal function of f to be

, centered at the point a ∈ Rn, and whose long side is parallel to the direction of the unit vector e ∈ Sn-1. Then for a locally integrable function f, we define the Kakeya maximal function of f to be

where m denotes the n-dimensional Lebesgue measure. Notice that  is defined for vectors e in the sphere Sn-1.

is defined for vectors e in the sphere Sn-1.

Then there is a conjecture for these functions that, if true, will imply the Kakeya set conjecture for higher dimensions:

-

- Kakeya maximal function conjecture: For all

, there exists a constant

, there exists a constant  such that for any function f and all

such that for any function f and all  ,

,

- Kakeya maximal function conjecture: For all

-

- (see lp space for notation).

Results

Some results toward proving the Kakeya conjecture are the following:

- The Kakeya conjecture is true for n = 1 (trivially) and n = 2 (Davies[8]).

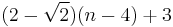

- In any n-dimensional space, Wolff[9] showed that the dimension of a Kakeya set must be at least

(n+2).

(n+2).

- In 2002, Katz and Tao[10] improved Wolff's bound to

, which is better for n>4.

, which is better for n>4.

- In 2000 Jean Bourgain connected the Kakeya problem to arithmetic combinatorics[11][12] which involves harmonic analysis and additive number theory.

Applications to analysis

Somewhat surprisingly, these conjectures have been shown to be connected to a number of questions in other fields, notably in harmonic analysis. For instance, in 1971, Charles Fefferman[13] was able to use the Besicovitch set construction to show that in dimensions greater than 1, truncated Fourier integrals taken over balls centered at the origin with radii tending to infinity need not converge in Lp norm when p ≠ 2 (this is in contrast to the one-dimensional case where such truncated integrals do converge).

Analogues and generalizations of the Kakeya problem

Sets containing circles and spheres

Analogues of the Kakeya problem include considering sets containing more general shapes than lines, such as circles.

- In 1997[14] and 1999,[15] Wolff proved that sets containing a sphere of every radius must have full dimension, that is, the dimension is equal to the dimension of the space it is lying in, and proved this by proving bounds on a circular maximal function analogous to the Kakeya maximal function.

- It was conjectured that there existed sets containing a sphere around every point of measure zero. Results of Elias Stein[16] proved all such sets must have positive measure when

, and Marstrand[17] proved the same for the case n=2.

, and Marstrand[17] proved the same for the case n=2.

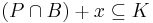

Sets containing k-dimensional disks

A generalization of the Kakeya conjecture is to consider sets that contain, instead of segments of lines in every direction, but, say, portions of k-dimensional subspaces. Define an (n,k) -Besicovitch set K to be a compact set in Rn containing a translate of every k-dimensional unit disk which has Lebesgue measure zero. That is, if B denotes the unit ball centered at zero, for every k-dimensional subspace P, there exists x ∈ Rn such that  . Hence, a (n,1)-Besicovitch set is the standard Besicovitch set described earlier.

. Hence, a (n,1)-Besicovitch set is the standard Besicovitch set described earlier.

-

- The (n,k)-Besicovitch conjecture: There are no (n,k)-Besicovitch sets for k>1.

In 1979, Marstrand[18] proved that there were no (3,2)-Besicovitch sets. At around the same time, however, Falconer[19] proved that there were no (n,k)-Besicovitch sets for 2k>n. The best bound to date is by Bourgain,[20] who proved in that no such sets exist when 2k-1+k>n.

Kakeya sets in vector spaces over finite fields

In 1999, Wolff posed the finite field analogue to the Kakeya problem, in hopes that the techniques for solving this conjecture could be carried over to the Euclidean case.

-

- Finite Field Kakeya Conjecture: Let F be a finite field, let K ⊆ Fn be a Kakeya set, i.e. for each vector y ∈ Fn there exists x ∈ Fn such that K contains a line {x+ty: t ∈ F} . Then the set K has size at least cn|F|n where cn>0 is a constant that only depends on n.

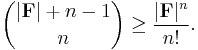

Zeev Dvir (2009) proved this conjecture for cn = 1/n!, using what Terence Tao called a "beautifully simple argument",[21] as follows. Dvir observed that any polynomial in n variables of degree less than |F| vanishing on a Kakeya set must be identically zero. On the other hand, the polynomials in n variables of degree less than |F| form a vector space of dimension

Therefore there is at least one non-trivial polynomial of degree less than |F| that vanishes on any given set with less than this number of points. Combining these two observations shows that Kayeka sets must have at least |F|n/n! points. It is not clear whether the techniques will extend to proving the original Kakeya conjecture but this proof does lend credence to the original conjecture by making essentially algebraic counterexamples unlikely.[21] Dvir has written a survey article on recent (as of 2009) progress on the finite field Kakeya problem and its relationship to randomness extractors.[22]

See also

Notes

- ^ Pal, Julius (1920). "Ueber ein elementares variationsproblem". Kgl. Danske Vid. Selsk. Math.-Fys. Medd. 2: 1–35.

- ^ Besicovitch, Abram (1919). "Sur deux questions d'integrabilite des fonctions". J. Soc. Phys. Math. 2: 105–123.

Besicovitch, Abram (1928). "On Kakeya's problem and a similar one". Mathematische Zeitschrift 27: 312–320. doi:10.1007/BF01171101. - ^ Perron, O. (1928). "Über eine Satz von Besicovitch". Mathematische Zeitschrift 28: 383–386. doi:10.1007/BF01181172.

Falconer, K. J. (1985). The Geometry of Fractal Sets. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–99. - ^ Kahane, Jean-Pierre (1969). "Trois notes sur les ensembles parfaits linéaires". Enseignement Math. 15: 185–192.

- ^ The Kakeya Problem by Markus Furtner

- ^ Alphen, H. J. (1942). "Uitbreiding van een stelling von Besicovitch". Mathematica Zutphen B 10: 144–157.

- ^ Cunningham, F. (1971). "The Kakeya problem for simply connected and for star-shaped sets". American Mathematical Monthly (The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 78, No. 2) 78 (2): 114–129. doi:10.2307/2317619. JSTOR 2317619. http://mathdl.maa.org/images/upload_library/22/Ford/Cunningham.pdf.

- ^ Davies, Roy (1971). "Some remarks on the Kakeya problem". Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 69 (3): 417–421. doi:10.1017/S0305004100046867.

- ^ Wolff, Thomas (1995). "An improved bound for Kakeya type maximal functions". Rev. Mat. Iberoamericana 11: 651–674.

- ^ Katz, Nets Hawk; Tao, Terence (2002). "New bounds for Kakeya problems". J. Anal. Math. 87: 231–263. doi:10.1007/BF02868476.

- ^ J. BOURGAIN, Harmonic analysis and combinatorics: How much may they contribute to each other?, Mathematics: Frontiers and Perspectives, IMU/Amer. Math. Soc., 2000, pp. 13–32.

- ^ Tao, Terence (March 2001). "From Rotating Needles to Stability of Waves: Emerging Connections between Combinatorics, Analysis and PDE". Notices of the AMS 48 (3): 297–303. http://www.ams.org/notices/200103/fea-tao.pdf.

- ^ Fefferman, Charles (1971). "The multiplier problem for the ball". Annals of Mathematics 94 (2): 330–336. doi:10.2307/1970864. JSTOR 1970864.

- ^ Wolff, Thomas (1997). "A Kakeya problem for circles". American Journal of Mathematics 119 (5): 985–1026. doi:10.1353/ajm.1997.0034.

- ^ Wolff, Thomas; Wolff, Thomas (1999). "On some variants of the Kakeya problem". Pacific Journal of Mathematics 190: 111–154. doi:10.2140/pjm.1999.190.111.

- ^ Stein, Elias (1976). "Maximal functions: Spherical means". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73 (7): 2174–2175. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.7.2174. PMC 430482. PMID 16592329. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=430482.

- ^ Marstrand, J. M. (1987). "Packing circles in the plane". Proc. London. Math. Soc. 55: 37–58. doi:10.1112/plms/s3-55.1.37.

- ^ Marstrand, J. M. (1979). "Packing Planes in R3". Mathematika 26 (2): 180–183. doi:10.1112/S0025579300009748.

- ^ Falconer, K. J. (1980). "Continuity properties of k-plane integrals and Besicovitch sets". Math. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 87 (2): 221–226. doi:10.1017/S0305004100056681.

- ^ Bourgain, Jean (1997). "Besicovitch type maximal operators and applications to Fourier analysis". Geom. Funct. Anal. 1 (2): 147–187. doi:10.1007/BF01896376.

- ^ a b Terence Tao (2008-03-24). "Dvir’s proof of the finite field Kakeya conjecture". What's New. http://terrytao.wordpress.com/2008/03/24/dvirs-proof-of-the-finite-field-kakeya-conjecture/. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ Dvir, Zeev (2009). From Randomness Extraction to Rotating Needles. ECCC TR09-077..

References

- Besicovitch, Abram (1963). "The Kakeya Problem". American Mathematical Monthly 70 (7): 697–706. doi:10.2307/2312249. JSTOR 2312249.

- Dvir, Zeev (2009). "On the size of Kakeya sets in finite fields". Journal of the American Mathematical Society 22 (4): 1093–1097. arXiv:0803.2336. doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-08-00607-3. MR2525780.

- Falconer, K. J. (1985). The Geometry of Fractal Sets. Cambridge University Press.

- Kakeya, Soichi (1917). "Some problems on maximum and minimum regarding ovals". Tohoku science reports 6: 71–88.

- Katz, Nets Hawk; Łaba, Izabella; Tao, Terence (2000). "An improved bound on the Minkowski dimension of Besicovitch sets in R3". Ann. Of Math. (The Annals of Mathematics, Vol. 152, No. 2) 152 (2): 383–446. doi:10.2307/2661389. JSTOR 2661389. http://www.emis.de/journals/Annals/152_2/laba.pdf.

- Wolff, Thomas (1999). "Recent work connected with the Kakeya problem". In H. Rossi (ed.). Prospects in Mathematics. AMS.

- Wolff, Thomas (2003). Lectures in Harmonic Analysis. AMS.